Italy Romanesque and Gothic Arts Part 6

In sculpture, Pisa reigns. While the Pisan Baptistery is garlanded with statues and jagged marble cusps, the Camposanto welcomes the remains of men into the land transported from Calvary, the cathedral raises its superb forehead near the bows tower. The sculptors run from Pisa to Lucca to decorate the beautiful San Martino; they run to Perugia to sculpt the fountain where the voices of virtues, liberal arts, the Bible and history resound among the jets; the prophets, the sibyls, Plato and Aristotle rush to Siena to erect the prophets, the sibyls, Plato, and Aristotle, who, in ecstasy or in the fury of inspiration, announce the coming of the Word or the eternal truth to the faithful. Italy was conquered with chisels by Nicola d’Apulia and his school.

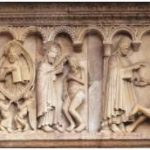

According to Globalsciencellc, Nicola (born in the early 1200s and died around 1280) marks the transition period between the Romanesque and the modern ages. Educated by the artists who worked for Frederick II in Puglia, he brings to Tuscany, Lucca, Prato, Pisa, Siena, Umbria, Perugia, the great classical art of the Apulian ambois and castles, and applies it to depict entire cycles of traditional Christian scenes. The pulpit of Pisa, more than all the other works, in which the collaboration of the followers takes over, gives us the knowledge of the art of Nicola d’Apulia, Roman for amplitude of forms, for classic drapery, for the great quiet of the orderly and massive compositions, still subject, like Romanesque sculpture, to the slavery of architecture. The forms, with their imposing structure,

In the art of Nicola’s son, Giovanni (circa 1250-circa 1320), the effects of movement succeed those of august composure; sculpture emancipates itself from the slavery of architectural plans; the gothic whirlwind overwhelms the agitated crowd of statues. Not Nicola d’Apulia, but Giovanni opens the new era of Italian sculpture. Already in Nicola the tendency to enrich the sculptural effect is announced progressively. In the pulpit of the cathedral of Pisa, the decoration is entirely subordinate to the architectural structure: the reliefs in leveled masses, despite the powerful construction of the form, are inserted in a methodical order within the rectangular mirrors of the polygonal parapet, and bundles of columns, three to three, they strengthen each vertex; the imperatorial figures of virtues reinforce the pillars of the arches, and the trefoil arches retain the full center. The first appearance of the pointed arch is in the pulpit of Siena, where Giovanni works for the first time next to his father, performing three bas-reliefs: the Crucifixion , the Elected , the Reprobate, in which new life erupts with sudden rebellion. The angels of John, in a corner of the pulpit, stormy, with cheeks swollen like those of the winds, launch the blasts of an advent of new art in the Gothic temple. Profound difference between the art of the two masters, which appears even more evident in the spring of Perugia, where from the polygonal compact and smooth tub, strengthened at the top by heavy bundles of columns, marked, in its massive grandeur, in the style of Nicola, lever the second, agile and broken; and from the second, with a faster leap, the bronze basin: smooth flower corolla into which the magnificent knot of nymphs and griffins plunges; nothing more than the art of Nicola, in this living flower born from the ardent imagination of Giovanni.

The Gothic triumphs with the pulpit of Pistoia in the lanceolate acuteness of the arches, in the cry of the statues, which no longer sit in the chair on the capitals of the columns, nor do they slowly recline within the corner of the pendentives, but give the idea of agitation from below. Faci for the enthusiasm of the movements, the rapid volute of the heads raised above the bodies, gathered in long tunics with sliding bundles of folds. Finally, in the pulpit of Pisa, destroyed by a fire, now rebuilt in the cathedral, the sculptural vegetation rises and descends along the increasingly broken walls, tightening, suffocating, hiding the skeleton of the building. A people of statues form the pedestals of the pulpit; the lions roar out among those forests of convulsive, frail figures, dominated by nerves, burned with fever: the double crowns of leaves on the capitals rotate in the wind in convulsions of flame; and the images of the bas-reliefs, dry, restless, passionate, erupt from the parapet, free in space, overwhelming the architecture; Nicola’s smooth and compact rock creaks, crumbles, breaks down into fantastic shapes. The sculptural forms free themselves from architectural slavery; they conquer space, reflecting, in the painful and feverish contortions, the fatigue of the struggle that led them to liberation.

The concept of independence of sculpture from architecture, greater in Giovanni’s Gothic than in French Gothic, informs the free sculptural vegetation that nestles between the edges of the facade of the cathedral of Siena: lions and dragons, and trampling horses, pushed out of the marble walls, cutting the wind that upsets the bristly manes. Next to that people of unleashed monsters, a people of seers – prophets, sibyls, ancient philosophers – dominate the crowd, shouting to the wind the truths of science and faith.

Not only Giovanni belonged to Nicola’s school. In addition to the mediocre Fra Guglielmo da Pisa, executor of part of the ark of S. Domenico in Bologna and of a pulpit in Pistoia, the noble spreader of the art of Nicola in Rome, Perugia, Florence, Arnolfo di Cambio ( 1232-1301), more faithful than Giovanni to the master, further away from Gothic impulses, tending to refine the forms of Nicola d’Apulia with Tuscan grace. He enriches his works with mosaic decoration, used in Rome by the Cosmati; it brings to art a profoundly Tuscan sense of measure, crystalline regularity of form in full Gothic period, virtuosity of marble processing, love of minute and subtle proportions, of marble sharpness. In the ciborium of Santa Cecilia in Rome, the Italian tendency to regulate the impetus of vertical lines by means of the brake of horizontal dividers, the Italian tendency to squaring, which characterizes our Gothic style in the face of the Gothic style of France, finds its full expression. Giovanni’s feverish life stops in the statuettes that adorn Arnolfo’s food and sepulchres, small and precious, with thinly stretched drapes, inert, almost fossilized bodies. Abstract, petrified and vague are the physiognomies of Arnolfian faces, with silent protruding eyes, without gaze; outlined with rare elegance the thin paper folds of the garments; stares at her small, ribbon-like hands. Refined marble worker, Arnolfo does not care to transfuse life into sculptures, satisfied with formal elegance, with the nobility of frozen forms, of subtle and profound measure.